EXERPTS FROM THE MEMOIRS OF EDDIE ALDREDGE – 1989

On March 7th, 1919, my parents and I stepped off the S.S. Okanagan into Kelowna. We had just come directly from England to Kelowna. It was a cold, nasty day and it was about four o’clock in the afternoon when we arrived. At this time, I was eleven and a half, born August 21st, 1901. My uncle, Arthur Good, had borrowed the democrat team from the ranch where he worked.

We got into this democrat, making our way out to Glenmore. Well, if you didn’t have one wheel drop into a very deep rut and the other one up over a rock, then it alternated side to side; you’d be standing still. On the ride, I began to have some reminiscences of being seasick crossing the Atlantic on the old Empress of Ireland, praying it would soon end. Then wondering how soon we would get to some sort of a decent habitation.

We arrived at the ranch which was owned by an American. Right next door was what was called the Company Ranch, and I saw that there was a big concrete flume that ran right through the upper end of that ranch. There were two houses and a small cabin on the ranch.

The small single-room cabin was for the Chinaman who worked on the fruit ranch. In one of the houses, my aunt and uncle, who then had two children, (they had more later), had to squeeze in room for my dad, mother and I; it was quite a job.

These buildings were all covered with a red tar paper. The Chinaman’s house was slightly coop-like and interesting. I upset my aunt no end, because within two or three days, I had made friends with the Chinese. The cook took great delight in stuffing me with things I could eat. Anything that was decent upset my stomach as I was of course, getting over being seasick and needed food, but that you shouldn’t do. In those days it was out of bounds to make friends with the Chinese. I couldn’t see the reason for that then and I can’t now.

We were in and about the ranch house on the Sunday, and they were going to hold the church service in the little schoolhouse which was directly opposite that ranch on the other side of the road. The three men decided to walk around by the road.

My aunt decided we would take a short cut across that orchard. The orchard had been wet from snow and rain, and one thing or another. All of us were crossing from a manure ring around a tree to the next manure ring, and when one would lose a rubber boot on that trip, another would lose a rubber on the next trip. I think we came out so that most of us had only one rubber before we got across. That was clay gumbo and when you stepped on that stuff, and then picked your foot up, you had two to four inches of mud stuck to that boot. You can figure just how nice that was.

Well, we got across and we managed to scrape the mud off and got to the church, all very well. Everything went nice and smooth and we went back home and got our meal.

Within two or three days I went with my eldest cousin who was then six, over to the schoolhouse to enrol. The school was taught by a little Englishwoman, very precise, trying to teach youngsters from Grade One to the Junior Fourth Reader. Me, having come out of what had been the Church of England Choir School, where the discipline was exacting and where they taught you and you learned, I promptly lost the equivalent of about four grades. Later I used to come home with my books and my mother wondered why I was not doing my homework, but I had gone through all that earlier.

My mother and father both got jobs at McCullough, on the construction of the Kettle Valley Railway. My mother was going up as cook and they hired someone to act as assistant cook, because my mother was only five feet tall, chunky and quite strong.

The previous cook had been working in the camp, and he had a piece of corrugated iron as a roof. They were setting off blasts near there and a piece of rock came through that tin roof and killed him. Pieces of rock were coming through even when my mother and father worked there. They didn’t stay very long. My father did the job as a bull-cook as he had for 18 years for the Great Eastern Railway in England.

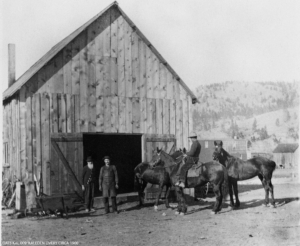

We came down and my father got a job working for an American; a fellow who got hold of Indian broncs, rode them out and resold them. My dad’s job was to use a spike-toothed harrow on the orchard that this fellow owned. My father knew horses well. The Great Eastern Railway employed men who could handle horses.

My father had learned a thing or two about horses. When my father saw his boss with a team and democrat heading for town, he called me and ordered me to stand at the gate to watch for him returning. I watched my dad. There were two big chunks of logs sawn off, three to four feet long, with a rope or cable through one end of each. He tweaked these. The broncs he was using were doing everything but paying attention. So, my father drove around where these chunks of logs were, and he heaved one chunk on each harrow, then took a lanyard from the horse’s bridle down to that log, and lengthened it to the point where if the horse tried to pull his head any other way than what was wanted, the log would be there. Dad started out on the field, then kicked one log off one side, then one off the other, so the horse was immediately on his bit, dragging that log through the field.

He had me by the gate for a specific reason – he did not want Mac to see what he was doing. I yelled when I saw Mac. Dad unhooked the logs and dropped them off, and by that time the team he was using was quite tame. Mac never learned what my father did, could never understand it and Dad wouldn’t tell him.

We moved from that ranch to Boyce’s Sawmill, south end of Kelowna, close to where the KLO Road and Pandosy meet now. Boyce’s Sawmill was close to the lake, and my dad got a job on the sawdust wagon, which was a two-wheeled dump cart. The horse was an old animal, a big one. He had an idea in hot weather of pulling the wagon down, sloping the sawdust pile in the lake, so he could cool off. Again, Dad got a lanyard on old Jim’s bridle; Jim came down, my father kept his lanyard, walked around the sawdust pile on the dock where the mill was, kept pulling that lanyard off the bit. Jim was in the water, his nose barely out of it. No more bath trick after that.

During the winter of 1913-14, my father only had a little work here and there, and my mother was doing housework. One day my dad was down on the old Kelowna dock and and the third mate of the S.S. Sicamous, was trying to hire more men to handle the loading of fruit on the boat. He told Dad that he was too slight to load, but Dad proved otherwise, by handling two extra boxes on his hand truck.

He went on to be deckhand, then to coal passer, cleaning out the ash pit and dumping coal from the bunker into the fire. Then he became a fireman. In the spring of 1915, March 7th, my mother and I stepped off the S.S. Sicamous in Penticton.

Late that year, my parents bought the original part of the house where I now live on Braid Street. My mother and I moved in about the second week of January, 1916. The lake was frozen over so Father couldn’t get home and the boat couldn’t into the Penticton steamer wharf for about three months. We had a cookstove, wood and that was all. We had no running water. There had been a well on the property, but it was defunct, so for weeks we melted snow for water.

The old part of the house; built by a man named Baker, was made with a kind of adobe, but he discovered that the clay and the climate in the Okanagan didn’t understand that language. He got some sort of a brick molder and got somebody to make cement bricks. Those bricks outside of the clay house are there today, after all those years. The main walls of the old part of the house are about 18 inches solid. The plaster was put right onto the clay and my mother used to wallpaper over that.

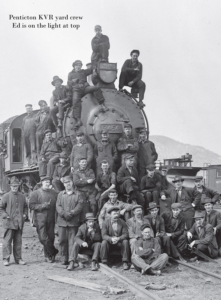

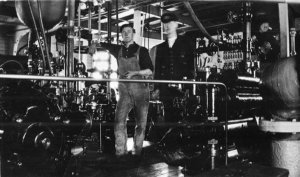

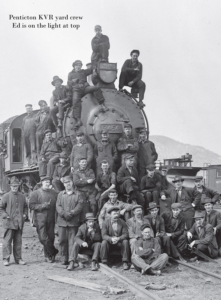

In 1916 my dad got some information that the Kettle Valley Roundhouse was starting up, so he got my mother – he always got Mother to do things, rather than do it himself – to go and see the master mechanic, a fellow by the name of Whitter. The result was that my father transferred from the Sicamous to the KVR roundhouse as machinist’s helper. He stayed there until he retired at the end of May 1941, just two weeks before I left to go to work on Naval Ordinance, which I did for four years.

My father enticed me to take a job with the Kettle Valley Railway so he could keep his eye on me. I quickly quit school to take on an apprenticeship as a machinist at the KVR shops. I lasted a few years in the heat and noise of the shops but always had a desire to do something cleaner.

An opportunity opened at the Mill in Trail for an electrical apprentice, so I headed for the Kootenays. This job was too much for me so I took a job at the Trail Bulletin as a reporter and copy writer. And so my long journalism career began.

I was back in Penticton by the mid-thirties to work for the Herald and to care for my parents after my father’s retirement. At this time I opened a small photography studio and called it “The Vest Pocket Studio”. It was on Robinson Street above the Chinese Restaurant.

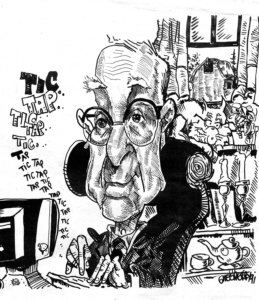

In 1950, I diversified my career by becoming a reporter for CKOV radio in Kelowna and even did a bit of freelancing for the Kelowna Capital News. I kept that position for 23 years. So as I was in my retirement years and still I was doing a lot of research for my column in the Okanagan Sunday edition, I thought I’d look into the origins of the Herald Newspaper. Here’s my perspective of it’s humble beginnings:

As of July 1906, Penticton had acquired its first newspaper, The Penticton Press. The type for the four sheet paper was all hand set – which meant that each of the thousands of individual letters had to be placed, individually, by hand into forms. Imagine doing that by the light of an oil lamp or a candle. The chief compositor was Everett Law, the “printer’s devil” or apprentice was Eric Murray, who in later years lost his left arm when a belt on the press caught it. At the earlier phase, Eric told me they had to turn the newspaper cylinder press by hand. A tough, heavy job that was but the paper couldn’t afford a steam engine to drive the press or anything else.

The paper occupied a small building at the corner of Smith (Front) Street and Main Street, on the site of the present Credit Union  building. In fact that former paper office was the first home of the Credit Union so it must have been quite well built.

building. In fact that former paper office was the first home of the Credit Union so it must have been quite well built.

W.H. Clement, the founder of The Penticton Press, had created a good small weekly despite the handicaps, not the least of which was perhaps, Clement himself. Courageous certainly, but the aloofness that marks the real newspaper man was not present. In other words he would get wrapped up in “causes” and while these did not slant his writing to too great an extent, (as has been the case with others who’ve started small newspapers) that aura of opinion was there. Certainly it did not make him too many friends and those who opposed him probably made it felt.

With the issue of July 2, 1910, a change came over the newspaper. With the July 2nd issue it became The Penticton Herald. Outwardly from its appearance (other than the name on the masthead) there was little change. But inwardly, there was a considerable alteration in input, coverage and intent.

The late Eric Murray told this writer something of these early days. Type had to be set by hand, which meant the placement of hundreds of fiddley bits of metal into the right places. That type had to be set by lamplight – it is hardly likely that the paper had a gasoline lantern, or even the acetylene lighting that was current in parts of Penticton at that time. A great deal of that typesetting was the work of Everett Law, who worked for the Herald until just a few years before his death. Just who else was on the paper in those early days is not known, but it is quite possible that the bulk of it was the work of Clement, Law, and young Eric. And not only the newspaper, but job-printing as well, for a good deal of the revenue for the shop had to come from job printing, naturally.

Somewhere between 1910 and 1915, the Penticton Herald moved from that little old building to what had been the Schubert Store at the foot of Vancouver Avenue. It was operating in that building when I came to Penticton, in March of 1915. About then was when I started with the Herald – selling newspapers, building up what I think was the first newspaper route in the infant town.

In 1914, I find that Senator Shatford sold his controlling interest in the Herald to a Vancouver newsman named Robert McDougall. Bob immediately moved a new “Linotype” printing press into the works, and redesigned the look of the weekly. Under his guidance, the paper grew so quickly that in 1917, the staff and machines moved into a new building on Nanaimo Avenue, the building now occupied by Judy’s Deli. The building was put up by Greer (a member of the 1910 council) and I think it was specifically constructed for the Herald. It was in this building that Eric Murray lost his left arm, it being caught in the belt that was pulling the flatbed press of that day.

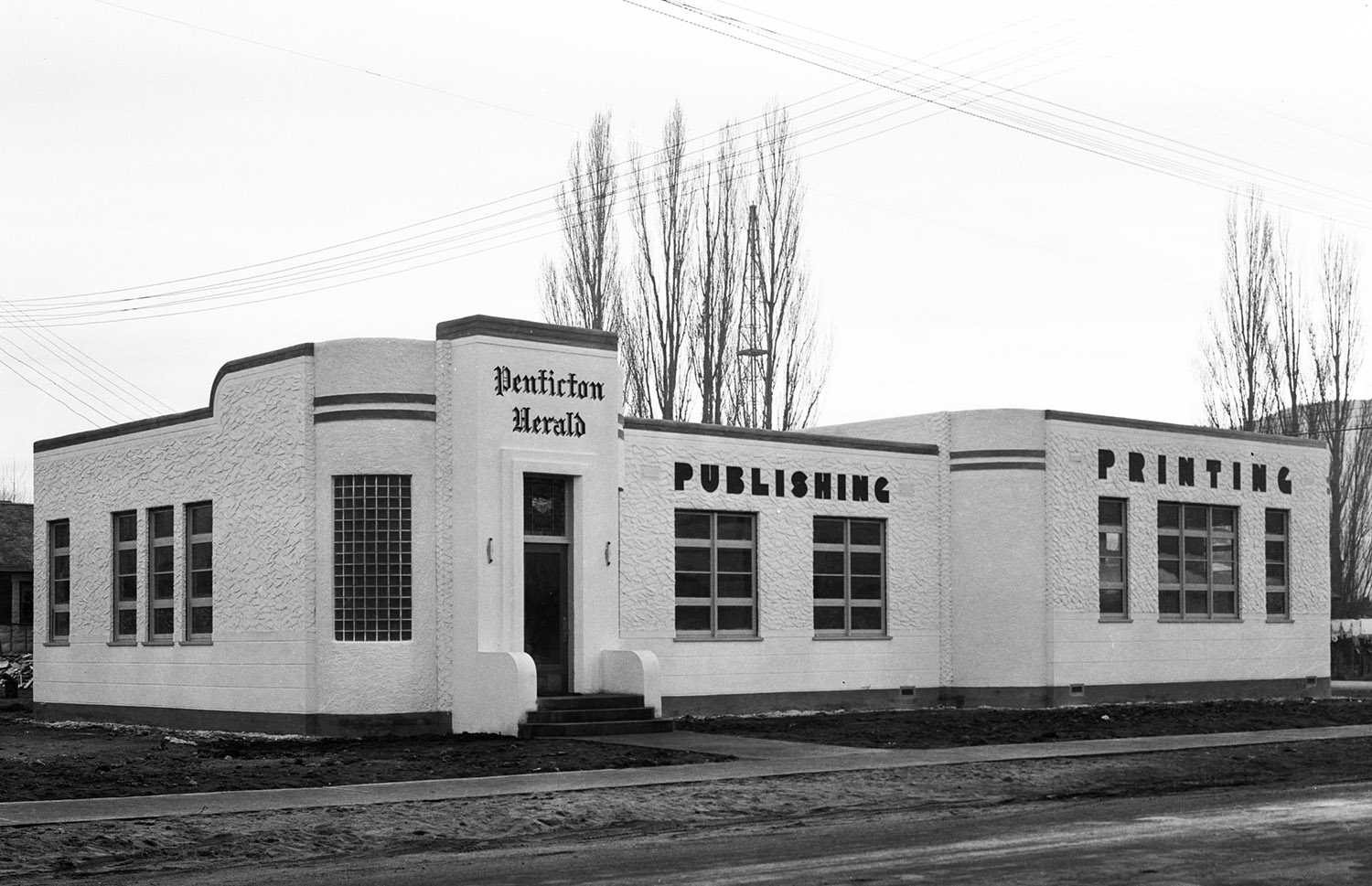

Robert McDougall kept his position at the Vancouver Province as city editor until 1927 when he finally brought his great talent to a full time capacity at the Penticton Herald. Mr. McDougall was able to guide the business through the dirty 30’s, until it outgrew its premises and moved, in 1939, to a new Art Deco style building across the street. This building was designed by famed architect Robert Lyon, who went on to be Reeve for 3 terms.

Robert McDougall made the Herald shine in the pre-war years and in 1938 the staff won the Mason Trophy awarded to the best weekly newspaper in Canada. Then they won the David Williams Cup for the best editorial page. But it didn’t end there; they won over and over, putting Penticton on the proverbial Canadian newspaper map.

R. J. McDougall passed the torch in 1940 to Greville Rowland, a fellow newsman from Vancouver, who became the new owner and publisher.

Mr. McDougall went on to become Reeve of Penticton for 2 terms, 1941-42 and 1945-46, competing in the polls with Robert Lyon. An able public speaker, Bob became a Toastmaster and Ambassador for Penticton even after his retirement to Vancouver. He died peacefully at 94. I enjoyed working for him.

Grev Rowland was a media wizard, investing in CKOK with Maurice Finnerty in 1950, and taking the Herald to a tri-weekly publication in 1954. On November 1st, 1954, the Herald was published every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday.

On October 4th 1956, Grev sold the Herald to the Thompson Publishing Group but remained as the publisher until his retirement in 1980.

The Thompson Group made some immediate changes with the installation of a huge tubular press capable of producing 20,000 newspapers an hour. The printing staff was increased until the Herald became one of the largest employers in town.

Then Penticton became one of only 104 cities in Canada to publish a 5 day a week newspaper. On Monday, September 9th 1957, the big press made the Herald a member of the Canadian Press Association as it continues to this day. In 1989, Saturday was added and in 2000, in part ownership with the Kelowna Courier, Penticton had a newspaper delivered 7 days a week.

Editors note: I met up with Eddy on the urging of Victor Wilson and Dan Lybarger. It was Spring of 1978 when I had my first Aldredge experience. He had somehow ended up with the “Stocks” studio camera and I wanted to add it to my extensive collection. I was able to purchase this wonderful Eastman 8×10 wood and brass artifact for quite a reasonable price as it was sprayed with Roxatone, a stucco-like paint. I knew I had a years work ahead of me to restore it, but I just had to have it. It never occurred to me to ask Ed if he actually owned it.

From this visit came a long and wonderful friendship and many more collector cameras for my shelf; some that I had to pay for twice, of course. Ed was able to come up with the most amazing collections of photographs and negatives from local and not-so-local photographers which he passed on to me for the archive OATS has created.

From his home on Braid Street, Ed continued into the 1990’s with a column in the Okanagan Sunday paper called “Okanagan Pioneers”. He was busy with his memoirs up to his death at 91. He passed away in his sleep in 1992.

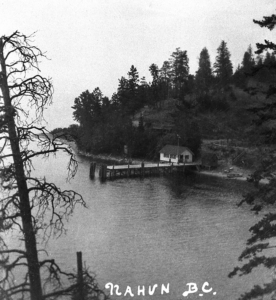

To give you a brief rundown on this most unusual gentleman, Old Kennard came to Canada from England well before the turn of the century and lived for many years at Nahun, on Okanagan Lake’s westside trail to O’Keefe Ranch. During his tenure, he kept a store and post office (he was the official Postmaster) that tended to about 40 people in the area.

To give you a brief rundown on this most unusual gentleman, Old Kennard came to Canada from England well before the turn of the century and lived for many years at Nahun, on Okanagan Lake’s westside trail to O’Keefe Ranch. During his tenure, he kept a store and post office (he was the official Postmaster) that tended to about 40 people in the area.

depression, after all.

depression, after all.

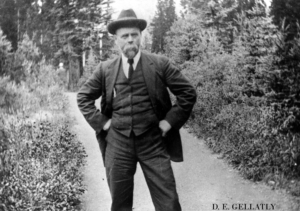

All their efforts depended on the water rights to the creek, and Mr. Gellatly made it clear with his neighbours that he would hold the rights. This caused considerable strife, but also led to the establishment of the Okanagan Irrigation and Power Company Ltd. The company offered 100,000 shares at $1 each with funds raised going to improvements and dams on Powers Creek. The surrounding farmers protested that they were buying into a project that they already owned and so the company folded before it began. What this did establish was Mr. Gellatly’s dominance in the area.

All their efforts depended on the water rights to the creek, and Mr. Gellatly made it clear with his neighbours that he would hold the rights. This caused considerable strife, but also led to the establishment of the Okanagan Irrigation and Power Company Ltd. The company offered 100,000 shares at $1 each with funds raised going to improvements and dams on Powers Creek. The surrounding farmers protested that they were buying into a project that they already owned and so the company folded before it began. What this did establish was Mr. Gellatly’s dominance in the area. Onions, tomatoes, and squash were shipped east right away. By 1903, there were berries, peas, beans, and melons harvested from between the rows of young fruit trees.

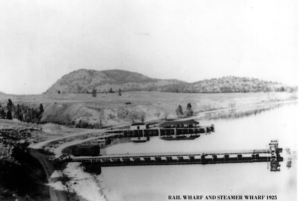

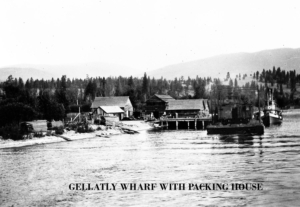

Onions, tomatoes, and squash were shipped east right away. By 1903, there were berries, peas, beans, and melons harvested from between the rows of young fruit trees. Even though the system was in place, it did not guarantee timely delivery. The system seemed simple enough. If you had between 3 and 5 tons of produce, you could load bushel boxes or sacks on the sternwheelers with handcarts. Each part of the shipment was delivered to a wharf or depot for pick up. If it was more than 10 tons you leased a freight car from CPR and loaded it yourself, then sealed it, and it would be unloaded by a broker in Calgary or Winnipeg, then delivered to the wholesalers. The hope was that the car would stay cool and dry and not sit on a siding for a week. CPR made you think it could deliver in 3 days.

Even though the system was in place, it did not guarantee timely delivery. The system seemed simple enough. If you had between 3 and 5 tons of produce, you could load bushel boxes or sacks on the sternwheelers with handcarts. Each part of the shipment was delivered to a wharf or depot for pick up. If it was more than 10 tons you leased a freight car from CPR and loaded it yourself, then sealed it, and it would be unloaded by a broker in Calgary or Winnipeg, then delivered to the wholesalers. The hope was that the car would stay cool and dry and not sit on a siding for a week. CPR made you think it could deliver in 3 days.

quite satisfied the fire was not caused by sparks from the Steamer “Sicamous”.

quite satisfied the fire was not caused by sparks from the Steamer “Sicamous”.

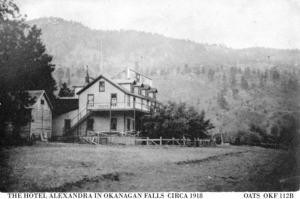

Many of the rooms faced north, offering a vista of the blue waters of the lake, nestled between grey-green hills that faded in the distance into the blue summer haze. The furnishings were lavish, in keeping with the anticipated development around the Falls and with the boom that extended across British Columbia.”

Many of the rooms faced north, offering a vista of the blue waters of the lake, nestled between grey-green hills that faded in the distance into the blue summer haze. The furnishings were lavish, in keeping with the anticipated development around the Falls and with the boom that extended across British Columbia.”

Within days of his return, he married Ellen Bassett, who he had courted prior to the war.

Within days of his return, he married Ellen Bassett, who he had courted prior to the war.

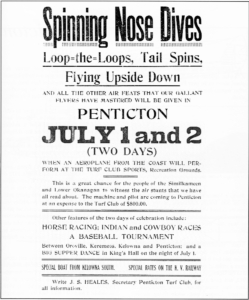

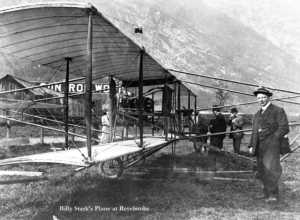

becoming the first aircraft to land at that city. He departed on Monday, August 4, for Vernon and arrived at Penticton August 6.

becoming the first aircraft to land at that city. He departed on Monday, August 4, for Vernon and arrived at Penticton August 6. Hugh Cleland was a member of the organizing committee working with Reeve George MacDonald for the event. Hugh recalls an impressive list of visiting aircraft in spite of the poor weather on the coast. A formation flying team named the Three Musketeers of the Aero Club of B.C. was flown by pilots A.H. Wilson, Maurice McGregor, and Don Lawson.

Hugh Cleland was a member of the organizing committee working with Reeve George MacDonald for the event. Hugh recalls an impressive list of visiting aircraft in spite of the poor weather on the coast. A formation flying team named the Three Musketeers of the Aero Club of B.C. was flown by pilots A.H. Wilson, Maurice McGregor, and Don Lawson.

Joe Weeks was only 15 when he arrived in Priest Valley from Shewsbury, England. He spent the hot summer of 1894 helping his father build a log home on their 14 acre farm near where downtown Vernon is today.

Joe Weeks was only 15 when he arrived in Priest Valley from Shewsbury, England. He spent the hot summer of 1894 helping his father build a log home on their 14 acre farm near where downtown Vernon is today. Trail and Nelson. Joe spent 3 years on the Slocan until he was transferred to the S.S. Moyie on Kootenay Lake. This mate’s job only lasted until Joe was accepted as mate on his beloved S.S. Aberdeen on Okanagan Lake.

Trail and Nelson. Joe spent 3 years on the Slocan until he was transferred to the S.S. Moyie on Kootenay Lake. This mate’s job only lasted until Joe was accepted as mate on his beloved S.S. Aberdeen on Okanagan Lake. In 1913, the Aberdeen, was retired, and Joe Weeks took his place on the tugs moving barges from railheads north and south. He worked the York and tugs Castlegar, Kelowna and Naramata. As he sailed the lake pushing freight barges, he watched longingly at the new luxury ship, S.S. Sicamous, that has been launched in 1914. She was one nice ship.

In 1913, the Aberdeen, was retired, and Joe Weeks took his place on the tugs moving barges from railheads north and south. He worked the York and tugs Castlegar, Kelowna and Naramata. As he sailed the lake pushing freight barges, he watched longingly at the new luxury ship, S.S. Sicamous, that has been launched in 1914. She was one nice ship.

While researching the former article on Captain Troup, I was puzzled with the lack of information on the training of steam boat pilots at the turn of the century. With the proliferation of sternwheeler construction, there would have been a logical need for trained, highly skilled crew members.

While researching the former article on Captain Troup, I was puzzled with the lack of information on the training of steam boat pilots at the turn of the century. With the proliferation of sternwheeler construction, there would have been a logical need for trained, highly skilled crew members.

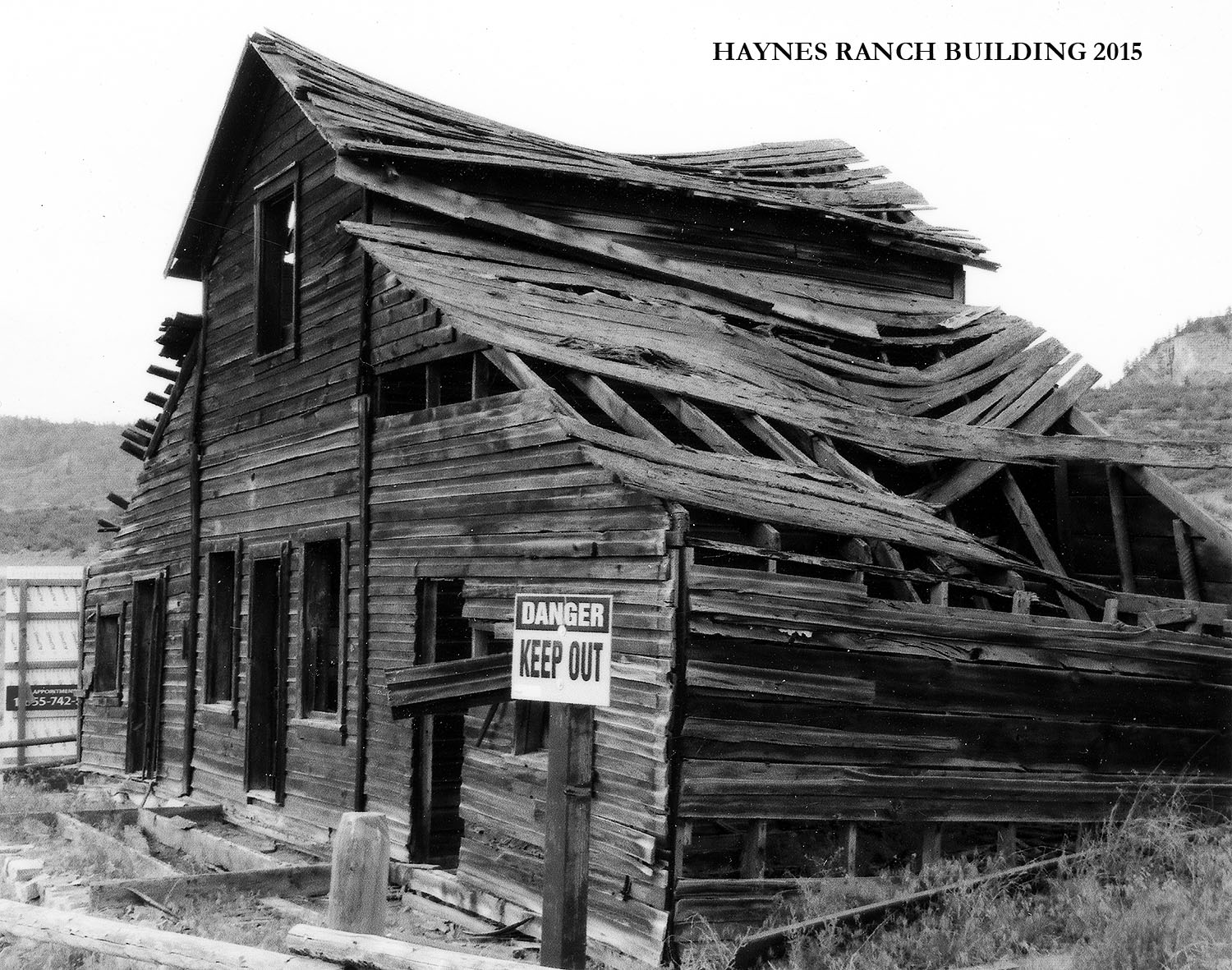

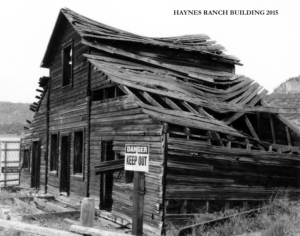

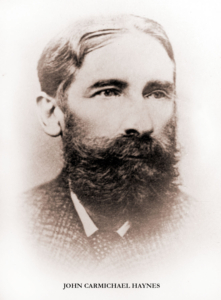

John Carmichael Haynes left Ireland in 1858, hoping to join the police force which Chartres Brew, a friend of his uncle and chief inspector of police, expected to establish in the new colony of British Columbia. They arrived in Victoria on Christmas Day 1858, and early in January 1859 Governor James Douglas appointed Haynes and Thomas Elwyn special constables to accompany Brew on an expedition to quell disturbances among the gold-miners at Hills Bar (site of McGowen’s war against the Spuzzum Natives). Haynes then served at Yale as a constable under Magistrate Edward Howard Sanders, and in November 1859 was promoted to acting chief constable.

John Carmichael Haynes left Ireland in 1858, hoping to join the police force which Chartres Brew, a friend of his uncle and chief inspector of police, expected to establish in the new colony of British Columbia. They arrived in Victoria on Christmas Day 1858, and early in January 1859 Governor James Douglas appointed Haynes and Thomas Elwyn special constables to accompany Brew on an expedition to quell disturbances among the gold-miners at Hills Bar (site of McGowen’s war against the Spuzzum Natives). Haynes then served at Yale as a constable under Magistrate Edward Howard Sanders, and in November 1859 was promoted to acting chief constable.

The Yosemite was part of a fleet run by John Irving.

The Yosemite was part of a fleet run by John Irving.  construction of a small steamer, Illecillewaet. He didn’t just start nailing boards together, but studied the weather, water levels and river channels. He needed to deal with ice jams and shifting sandbars like never before. To deal with times of low water levels, he adopted the stern-wheel to operate in shallow water. With the instant success of this little ship, the Columbia and Kootenay Steam Navigation Company directors notified James Troup that he had a free hand to construct similar ships to run its freight routes to the Kootenay gold fields.

construction of a small steamer, Illecillewaet. He didn’t just start nailing boards together, but studied the weather, water levels and river channels. He needed to deal with ice jams and shifting sandbars like never before. To deal with times of low water levels, he adopted the stern-wheel to operate in shallow water. With the instant success of this little ship, the Columbia and Kootenay Steam Navigation Company directors notified James Troup that he had a free hand to construct similar ships to run its freight routes to the Kootenay gold fields. the first with an electric lighting system to the delight of those on board and off.

the first with an electric lighting system to the delight of those on board and off.

power to the transmitter would be immediately lost. The wireless operator, W.R. Keller, knew this. He was unable to transmit an SOS before power was lost to the ship, and so he ran below decks and found a functioning electrical connection with the engine room’s lamp battery. Using this power, he was able to send a short message that simply said, “S.S. Princess May sinking Sentinel Island; send help.”

power to the transmitter would be immediately lost. The wireless operator, W.R. Keller, knew this. He was unable to transmit an SOS before power was lost to the ship, and so he ran below decks and found a functioning electrical connection with the engine room’s lamp battery. Using this power, he was able to send a short message that simply said, “S.S. Princess May sinking Sentinel Island; send help.”

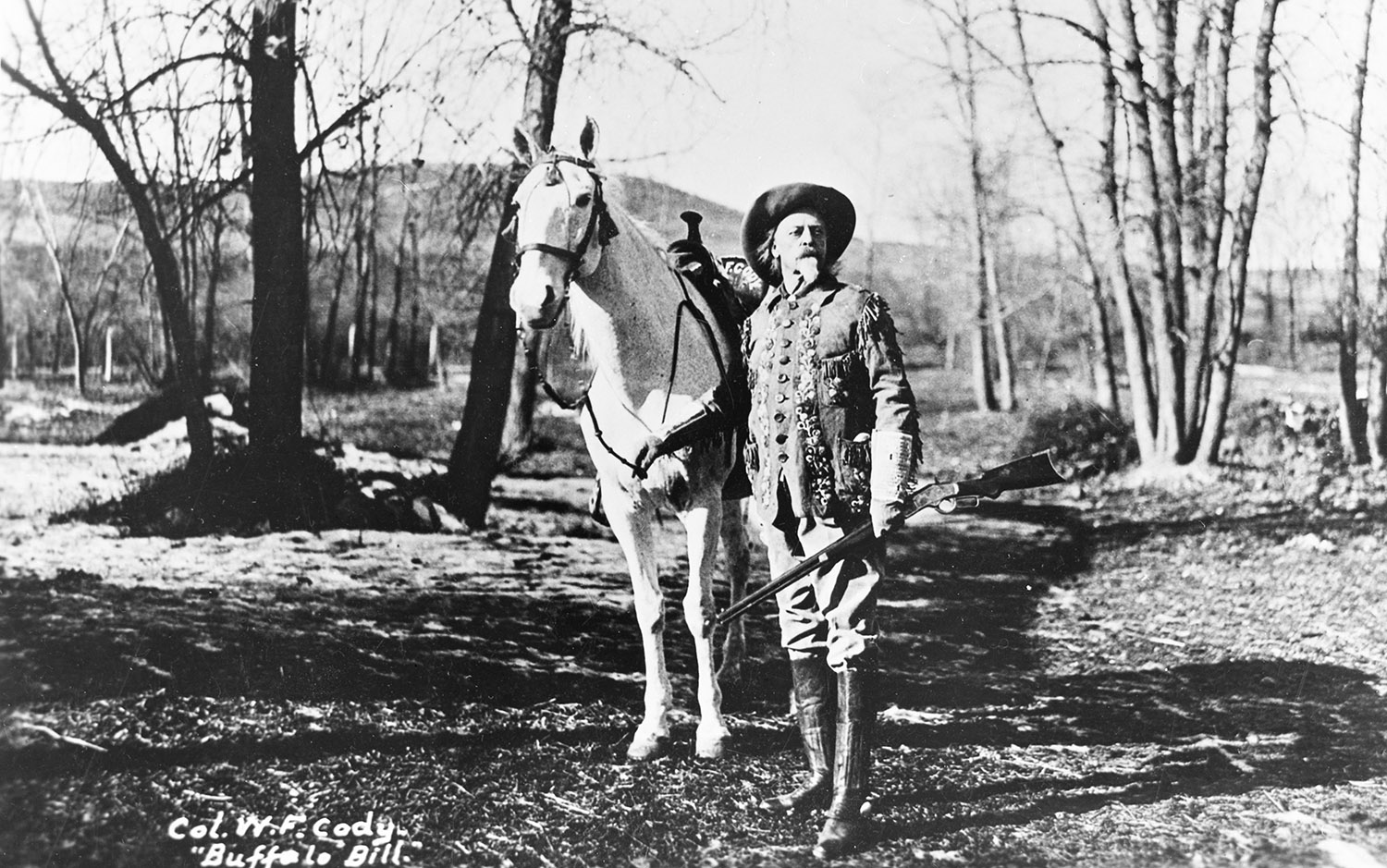

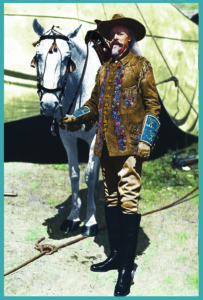

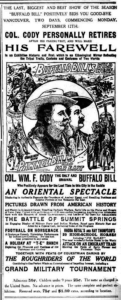

As Editor, I must confess that I have used an age-old method of creating an eye-catching cover that has little to do with local history. Saying that, I admit a fascination for the dynamic, bigger than life performances of the Wild West Show. In such I have gathered dazzling photographs of western life for the OATS archive. The cover is my favourite.

As Editor, I must confess that I have used an age-old method of creating an eye-catching cover that has little to do with local history. Saying that, I admit a fascination for the dynamic, bigger than life performances of the Wild West Show. In such I have gathered dazzling photographs of western life for the OATS archive. The cover is my favourite.

“The seating capacity of the big arena in which the exhibitions are given … is ordinarily 14,700. But the overflow amounted to 1,700 or more, swelling the total of attendance to 16,400. (Another) 3,000 to 4,000 persons were turned away.”

“The seating capacity of the big arena in which the exhibitions are given … is ordinarily 14,700. But the overflow amounted to 1,700 or more, swelling the total of attendance to 16,400. (Another) 3,000 to 4,000 persons were turned away.”

building. In fact that former paper office was the first home of the Credit Union so it must have been quite well built.

building. In fact that former paper office was the first home of the Credit Union so it must have been quite well built.