THE BLAKEBURN MINE DISASTER AUG. 13, 1930 Coal is everywhere on the mountains in the Tulameen Valley. The veins of anthracite to the southwest of Coalmont are some of the best in the world and with the completion of the Kettle Valley railway in 1915 this coal could be shipped throughout the world.

Coal is everywhere on the mountains in the Tulameen Valley. The veins of anthracite to the southwest of Coalmont are some of the best in the world and with the completion of the Kettle Valley railway in 1915 this coal could be shipped throughout the world.

The town of Blakeburn opened for business in 1920 and construction of trams, tipples, powerhouses, and mine-rails were completed to the mouths of the underground shafts by 1921.

Major investors, Blake Wilson and Pat Burns (the meat king) put the call out for miners. They came from all over the world to carve coal out of the bedrock, Scots, Poles, Yugoslavs and locals alike.

A community grew on the heights far above the valley, complete with stores, homes, school, tennis courts and sports fields. There were hockey teams, Baseball teams and a pipe band.

In its first years of operation, the collieries averaged 450 tonnes each day to the rails at the base of the tram. Operations didn’t cease until 1940.

It was the devils own work; hot and dusty; and the wages were low for grunt work. These men ate, slept and breathed coal dust for the majority of their short lives.

On August 13, 1930, 45 of them were killed.

It wasn’t the worst coal mine disaster in B.C. history, but it was fifth. The worst was in Nanaimo in 1887 when 148 men lost their lives to a coal explosion. But this was 1930 when safety and training was always in the forefront. Blakeburn’s rescue team won awards for first aid and rescue drills in1929 and 1930, and years after.

Number 4 shaft had had its problems prior to the explosion. A committee was formed of miners to deal with the “after-damp” in some of the caves and sills deep in the mine. When temperatures rose in some of the tunnels, they were walled over and sealed to keep carbon monoxide from leaking into the work areas. Ventilation was well served from the vents and fans.

The day of the explosion was a stormy one with considerable lightning over thick, muggy air; a typical August day where your sweat wouldn’t dry. Somehow the methane gas built up behind one of the walled-up caves. What caused it to ignite is not known but when it did, shaft number 4 came apart.

Moments before, Johnny Porchello had just waved motorman Harry Whitlam out of the shaft with 30 cars and proceeded back into No. 4. He got about 700 feet in when the lights flickered, then came on again; and then blackness. He heard a thunderous sound from deep below and dropped flat on the ground. The blast struck him and when he came to, everything was a blur. He crawled slowly forward and soon struck water. Realizing he was going the wrong way, he turned, half crawling, half running and made the entrance through the dust and rocks. Johnny was the only one to get out. Of the 46 miners, 45 were still inside.

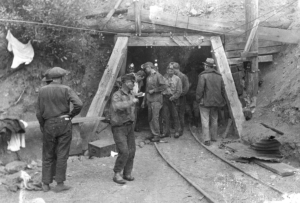

Inspector Biggs, with the clipboard and Harry Hopkins, far right assess the entrance to No. 4.

Fresh timbers have replaced the damaged ones at the entrance and debris is cleared.

The miracle of his survival was noted in the debris that was thrown from the mouth of the shaft. A power pole was sheered off 10 feet from the ground by a rope guide reel. The reel was attached to a mine timber well down from the entrance.

Dave Gilmour was cutting wood in a shed near the portal of upper No. 4 when the blast occurred. The roof of the shed blew off and the walls collapsed with him and his children inside. Fortunately, no one was injured.

It was thought that the force of the explosion was almost spent when it reached these areas; but imagine the sheer intensity of the blast having occurred 3000 feet below ground.

The alarm went off immediately and miners from the other shafts were evacuated and rushed to the mouth of the shaft and began removing debris. Mines Inspector, John Biggs was at the Wilson tunnel and arrived within 15 minutes to assess the tragedy. He and pit boss Harry Hopkins began barking orders to begin rescue operations.

After an explosion like this, the power goes out to the ventilation system and after-damp or carbon monoxide gas starts to build up. If any miners survived the explosion, they would succumb to the gas within minutes, so time was of the essence.

It was noted that Blakeburn mines were free of gas in inspections by the Ministry of Mines since the mine opened. So there was a sense of hope and those involved with this rescue needed that hope.

As the rescue teams worked into No.4, it was evident with the discovery of the first bodies that gas was thick inside. Rescuers fled to get oxygen tanks then re-entered and continued. Then as they broke through debris at slope 2, they discovered 12 miners who only had enough time to chalk a note “up here” before they died. It was evident that hope was gone for anyone to have survived. They were now working to recover their friend’s bodies.

Fire had broken out in shafts 5 and 6 and smoke made progress impossible. Crews were able to reseal these fire areas by the 16th, and then it broke through again on slope 15 causing a cave-in that made further exploration difficult.

There was much heroism in days to come as men worked without a break. The threat of further explosions and shaft collapse were ignored by these souls as they drove to reach the depths of the mine. They had to pump water from the depths and use canaries to check gas levels. Every foot beneath was fraught with mortal danger and hopelessness.

They recovered the last of the miners on the 10th of September.

Of course there was a lengthy investigation and in a report by Chief Inspector of Mines, James Dickson, the cause was undetermined. He stated “Some witnesses reported a vivid flash of lightning in the vicinity of the mine portal at the exact minute of the explosion. All electrical cables are fitted with lightning arresters both inside and out. All arresters were found to be without signs of fusion and remained in order.”

“Apart from the distance this explosion travelled, there is no indication that coal dust played an important part. “

“The coal from this district is very subject to spontaneous combustion, and in this No. 4 mine there are a number of areas that have been sealed off on account of fire or heating. There was a decidedly high temperature in the accessible area after the explosion even after allowing for the fact that the ordinary ventilation was cut off. The entire area is now sealed off as a precaution.”

“In view of the serious loss of life due to this explosion and the difficulty in ascertaining the exact cause, I respectfully recommend that an investigation be made with a view to determining the exact cause and if possible, help to prevent such as disaster from happening again.”

This investigation was completed in October of that year and independent investigator, Thomas Graham concluded: “The lines of force clearly indicate that the source of the explosion was in the worked-out area of No. 1 slope off No. 15. The build up of gases from a heated gob in a stopped off area was the ignition point of this explosion. I am unable to arrive at a definite conclusion as to the cause or point of ignition.”

Several miners candidly reported “hard times in the mines” and rules were broken by all level of workers. This job was important and holding on to it was the difference between subsistence and sheer poverty. No big rules were broken but the job was everything so you said nothing and survived.

Manager George Murray told all rescuers that they would be paid for the hours spent in the rescue but none claimed the pay. “I couldn’t ask for pay to rescue my friends trapped in the mine.” said one worker.

A few days after the disaster, the Blakeburn Relief Fund was set up by the Princeton Board of Trade to raise funds for the widows and children. Local businessman W.A. Wagenhauser chairman, and news editor Dave Taylor was secretary. A letter was sent to all major municipalities in the province pleading for assistance. The response to the letter was overwhelming and money poured in from all over the country and, the world. The Vancouver Province alone brought in over $7,000. By the time the drive concluded, donations reached $86,000.

The fund was dispersed by the “Permanent Committee” at Blakeburn. Each widow received $20 a month with $10 for each child, to continue as long as the fund lasted. For some who requested, a ticket to the “old country’ would be provided in lieu of the pension. It seems five families accepted. Some also received a small amount from Workers Compensation Board, although the amount is not known. Forty-two of the miners are buried in Princeton Cemetery. The funerals were quite an event with a long cavalcade of hearses, flat beds and cars proceeding to the cemetery.

In its history, Blakeburn had 56 fatalities, but this 1930 disaster changed the way the Ministry of Mines promoted mine safety and support to rescue teams. Technology was introduced to make the rescue and recovery far quicker and safer for all concerned.

STATISTICS:

Among the dead at Blakeburn were:

Yugoslavia -Mike & Zeko Lubardo Brothers – buried together

Scotland -William & Peter Smith Brothers – buried next to each other

Yugoslavia -Frank & Joseph Stanich Brothers – buried together

Youngest – William Sim – 17.5 years old

Oldest – William O. Ross – 64 years old

Average age – 34.5 years

Employed shortest period of time:

Frank Gailus – 9 days

Employed longest period of time:

William Ross – June 30, 1921

Thomas Gibson – September 29, 1921

Clifford A. Smith – 1921

12 – born in Scotland 1 – born Germany

14 – born Yugoslavia 1 – born Lithuania

3 – born England 1 – born Ireland

3 – born USA 2 – born Poland

5 – born Canada 3 – born Russia

17 single men, 26 married men, 2 widowers

Sources

Blake, Don: Blakeburn,From Dust to Dust 1982

Currie, Laurie: Princeton, BC 1990

The photography of Howard McInroy

and the research of Lori Weissbach