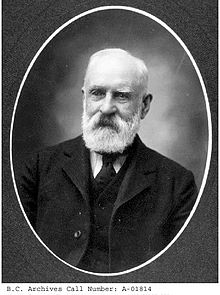

Walter Moberly was one of the great builders in B.C. History, and he ranks with explorers like Alexander MacKenzie, and David Thompson. He participated in two great achievements in the early development of British Columbia. These were the construction of the Cariboo road and the survey for an overland railway across British North America.

Walter Moberly was one of the great builders in B.C. History, and he ranks with explorers like Alexander MacKenzie, and David Thompson. He participated in two great achievements in the early development of British Columbia. These were the construction of the Cariboo road and the survey for an overland railway across British North America.

In spite of his accomplishments he was not honored in his time and has not been duly recognized since.

Moberly possessed tremendous energy and enthusiasm and was unquestionably a great engineer. The great dream that drove him on was the charting of the route for a transcontinental railway close to the U.S. Border, which would link Canada from coast to coast and hold the country for the Queen.

Walter spent much of his youth in Barrie, Ontario. Here he became acquainted with the daughter of Colonel Bernard. She later became the wife of Canada’s Prime Minister, Sir John A. MacDonald. The friendship of these three continued over many years and later proved to be a significant factor in the construction of the CPR.

Between the years 1854 – 1857, Moberly spent much his time exploring the region north of Lakes Huron and Superior. It would seem that even then he had a passion for exploring and already had the idea of a transcontinental railway across Canada. In his notes he said: “They were the first explorations made that had in view, a future transcontinental railway.”

It was during the winters of those years, that he became acquainted with the artist, Paul Kane. Kane had just returned from an overland journey to the Pacific Coast under the leadership of Sir George Simpson, governor of Hudson’s Bay Company. Kane imparted to his eager listener a great deal of information about the vast extent of territory he had traversed.

By that time, Moberly had become convinced that a transcontinental railway was the only way to secure British North America’s future as a nation. Accordingly, when he learned in 1857, that the British Government was sending out an expedition under Captain Palliser with the purpose of finding a route to the Pacific Coast, Moberly made plans to meet the captain.

News of the first gold strikes on the Fraser River spurred on Moberly. To obtain funds to carry out this great plan, he sold out all his timber holdings in Ontario, and through Kane, obtained a letter of introduction from Sir George Simpson, governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company, to Sir James Douglas, governor of British Columbia.

In San Francisco, he found a ship bound for Esquimalt, and reached that port late in 1858. He walked over a muddy road to Victoria, where he found the little town full of gold miners who had taken part in the first gold rush to the gravel bars on the Fraser River.

He called upon Governor Douglas, and was immediately offered an appointment in the government service. Moberly declined because he wanted to meet Captain Palliser and to be free to carry out his own explorations.

Governor Douglas gave Moberly his best wishes and a letter to the factors of the Hudson’s Bay Company requesting their co-operation. The governor also asked Moberly to report on the feasibility of the Harrison Lake-Lillooet route to the interior.

Early in 1859 Moberly crossed the Gulf of Georgia on the steamer Otter to Fort Langley, where he met William Yate, chief factor on the Fraser River.

Next day he proceeded up the Fraser on the stern-wheeler Enterprise, the first steamer to navigate the river to Yale, under “that prince of good fellows, Capt. Tom Wright.”

At the mouth of the Harrison River he disembarked and secured a canoe at a neighboring native village, and paddled to Fort Douglas at the head of Harrison Lake. He found the post full of miners and packers en route to the interior, and followed this route up the Lillooet River to Lillooet Lake and then portaged eastward to the Fraser. Moberly recorded the journey in his diary as a cold and miserable experience. Lack of food forced him to return to Fort Langley. He was convinced that this was not a suitable route for a railway.

He then returned to Victoria and reported to Governor Douglas. He advised that certain improvements could be made on the portages on the Harrison-Lillooet route and at the rapid on Harris River. These reports were the first regarding public works on the mainland of British Columbia. When Colonel Moody of the Royal Engineers arrived these plans were approved and quickly carried out. Moberly also reported favorably on the site of the present city of New Westminster as being an excellent location for a capital.

Early in 1859, at his own expense, Moberly made preparations for his exploration along the Fraser and he examined the formidable canyons between Yale and the Thompson River. He again reported to Governor Douglas that a wagon road or a railroad, while it would be costly, was more than possible.

In August the energetic Moberly cut a trail through the dense forest from New Westminster to the site of Port Moody on Burrard Inlet. He described the fine harbor stretching seaward as a suitable site for the terminus of a trans-continental railway.

On his return to Coal Harbor from Howe Sound he pre-empted waterfront land on the site of Vancouver city which he thought an ideal site for a great port.

He spent the winter of 1859-1860 in Victoria where he met Captain Palliser and Doctor Hector and other members of their party. They had reported to Governor Douglas, that after a thorough examination of the passes, they were of the opinion that a railway could not be built through the mountains of southern British Columbia because of the impassable coast range. This was very discouraging to Moberly who had spent most of his personal wealth in this exploration. Governor Douglas refused government backing for any further search for a route for a transcontinental railway.

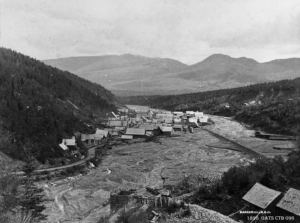

The great bluff at mile 88 of the Thompson River stretch of the Cariboo Trail was part of Moberly’s section completed in 1864. It remained in service well into the next century. This photo was taken by Notman photographer Benjamin Baltzly, and is part of the Stocks Collection.

In the interval before Moberly’s participation in the building of the Cariboo road, he worked with Edgar Dewdney, in the surveying of the Dewdney Trail eastward from Hope through to the Similkameen country.

By 1860 it was felt that the main gold fields of B.C. would be found in the upper Fraser, in the Cariboo. Alfred Waddington proposed a route eastward from the head of Bute Inlet. A Mr. Green advocated a more northerly road from the head of Bentinck Arm where Bella Coola is now located as a less rugged route. Interests in Victoria hoped that one of these two would be adopted. Governor Douglas himself favoured the old Harrison-Lillooet route, but Moberly persuaded Moody to support the Fraser Canyon route and the two together finally won over the governor.

Then Waddington’s party met with disaster. The Natives of the district had become hostile through grievances, and they attacked and wiped out Waddington’s party. The Natives responsible were tried and hanged by a court presided over by Judge Begbie.

Moberly then formed a partnership with Charles Oppenheimer and T.B. Lewis to build the

Cariboo Trail. The government granted a charter, giving them the right to collect road tolls, and provided them with subsidies to help finance the construction.

Construction of the road was to be in sections: Yale to Chapman’s Bar was to be the task of Captain Grant and the Royal Engineers; Joseph Trutch was to build the stretch from Chapman’s Bar to Boston Bar; Thomas Spence to extend the road from that point to Lytton; Moberly’s firm was to build along the Thompson River and link with G.B. Wright’s section, which was to be built northward from Alexandria.

Moberly was to locate the right-of-way, Lewis was to be in charge of accounts, and Oppenheimer was to secure supplies and finances.

From the beginning there were not only the expected difficulties of building a road through very rugged country, but many unforeseen difficulties as well. Men had to carry everything over the most difficult of trails. There was very little machinery to supplement manpower in the task of carving the road through the canyons. Labor was scarce and undependable, as men were continually quit their jobs to rush off to the gold fields. Their Indian packers did not prove dependable; Chinese labor, on the other hand, proved very satisfactory. Besides all this, the financial support for the government was not forthcoming as the contractors expected. In 1862 Lewis withdrew in disgust. Moberly bought out his interest in the firm. To keep the work progressing, Moberly on his personal note, borrowed money to pay his men.

It was arranged that Oppenheimer would call on the government and try to get an advance. Meanwhile Moberly kept the work going and located a route for the road from Ashcroft to Clinton.

Troubles accumulated. Oppenheimer reported that he could get no more money. The men were clamoring for wages so Moberly decided to travel to see Governor Douglas in New Westminster. He succeeded in securing an advance of $6000 and the promise of the balance of $50,000. At Yale he found that many of the men had left because they thought Moberly was skipping the country. His men were paid out of the $6,000 and then he proceeded to Lytton where he waited for the expected government certificates. Instead, he was informed that the contract was cancelled for non-fulfillment of the terms of the agreement between his company and the government.

Moberly asserted his rights for compensation for work already completed and for the equipment and supplies on the job. However, he pulled back as he felt it was in the interest of the public and, vital to the development of the new colony, that the road be pushed through as rapidly as possible. He accordingly turned over all his interests to the government and volunteered to serve as a superintendent under other government contractors. In 1864, in association with J.B. Wright, the last section of the road was built from Alexandria through Quesnel to the Cottonwood River and on to Lightning Creek and Barkerville. The idea of a rail route across the mountains remained his fixed purpose. So, in 1864, he handed over his department to J.W. Trutch and laid plans for the task ahead. Several routes seemed possible, but all appeared to be difficult and expensive. The first of these choices was by way of the Fraser Canyon, the North Thompson River, via Yellowhead Pass to Edmonton. This was felt to be too far north and would perhaps permit the southern part of the country to fall into the orbit of the United States. A second route that seemed a possibility was by way of the Fraser River and the South Thompson, then by a maze of canyons to the Columbia and the Great Bend, then to the Blueberry River and Howse Pass across the Rockies. A third route was by another series of canyons through the high Selkirks to the Kicking Horse Pass.

The idea of a rail route across the mountains remained his fixed purpose. So, in 1864, he handed over his department to J.W. Trutch and laid plans for the task ahead. Several routes seemed possible, but all appeared to be difficult and expensive. The first of these choices was by way of the Fraser Canyon, the North Thompson River, via Yellowhead Pass to Edmonton. This was felt to be too far north and would perhaps permit the southern part of the country to fall into the orbit of the United States. A second route that seemed a possibility was by way of the Fraser River and the South Thompson, then by a maze of canyons to the Columbia and the Great Bend, then to the Blueberry River and Howse Pass across the Rockies. A third route was by another series of canyons through the high Selkirks to the Kicking Horse Pass.

The greatest obstacle was the Gold Range, which seemed to be unbroken and impenetrable. Moberly’s party, with Albert Perry and two Indians explored the area east from Kamloops. The discovery of Eagle Pass is undoubtedly the best-known incident of the life of Walter Moberly.

He ascended the Eagle River, which flows westward from the Gold Range, and climbed to a peak where he had a wide view of the rugged area. He observed eagles flying directly into the seemingly unbroken wall of the mountains where they disappeared. A careful examination of the area fulfilled his hopes and Eagle Pass was discovered. Moberly blazed several trees, and reminiscent of that earlier trailblazer, Alexander MacKenzie, he wrote in colored chalk: “This is the route of the overland railway.”

“I then knew that an imperial highway of the greatest value to the British Empire and to British North America was a certainty, and I felt gratified that the years of toil, of hardships, of privation and expense I had incurred, would be of great and lasting benefit to my native and adopted countries – England and Canada.”

They then examined the Illecillewaet, hoping to locate a good pass through the Selkirks. An incomplete examination gave promise of success here too. But winter forced Moberly to suspend operations. And in the following year, 1866, Perry carried out an exploration and found the route through the Selkirks, later named Rogers Pass.

In 1866 Moberly explored the Big Bend of the Columbia from Golden to Revelstoke, and the Kootenays south to the Crowsnest Pass. He also improved the Dewdney Trail from the Similkameen to the Okanagan.

After this season’s labour was completed, he returned to New Westminster and reported to Governor Seymour. They disagreed sharply and in an angry moment, Moberly was fired as assistant surveyor-general. No subsequent offers made by the governor could placate Moberly, who announced that he was going to the United States to see what was going on there.

For four years he traveled and worked in the western United States, but kept in touch with developments in Canada. In 1871, he heard that confederation with Canada was being discussed in B.C. and that the most vital of the terms was the promise of a transcontinental railway. So he hastened back to Canada and sought an audience with his old friend, Sir John A. Macdonald. He explained his views on the matter of the transcontinental railway and suggested the route that it should follow.

Sanford Fleming was appointed engineer-in-chief and under him Moberly was to be in charge of surveys in B.C. Numerous parties were sent out under Moberly’s direction. John Trutch was in charge of surveys between Burrard Inlet and Kamloops; a Mr. Mohun was to make surveys in the Eagle Pass region; Gillette was sent to make a survey of the Howse Pass area, and Roderick McLennan was to examine the North Thompson and the Yellowhead Pass. Moberly favored the Big Bend of the Columbia route to Howse Pass. Under difficult weather conditions Gillette completed his examination and reported that a good line, though steep, could be made through Howse Pass. His surveys could not be completed because of snowstorms and they were forced to withdraw to winter quarters at Boat Encampment on the Columbia. This report confirmed Moberly’s opinion that it was a practical route. He had crossed the pass earlier that season to meet his brother, Frank, who was surveying on the Alberta slopes of the Rockies.

Moberly favored the Big Bend of the Columbia route to Howse Pass. Under difficult weather conditions Gillette completed his examination and reported that a good line, though steep, could be made through Howse Pass. His surveys could not be completed because of snowstorms and they were forced to withdraw to winter quarters at Boat Encampment on the Columbia. This report confirmed Moberly’s opinion that it was a practical route. He had crossed the pass earlier that season to meet his brother, Frank, who was surveying on the Alberta slopes of the Rockies.

Just before the opening of the new work season, and to his consternation, he received word that the Yellowhead Pass had been chosen, and the orders directed Moberly to conduct the necessary work there. He was angry and disappointed at this unexpected change in plans. And so in trying to have everything well organized and in readiness, he had incurred heavy expenses, and gained the displeasure of Fleming who censured him for exceeding his authority. Moberly’s resentment was increased by his firmly entrenched opinion that a line through the Yellowhead was too far north to hold the southern territory for Canada. He recovered his pack trains and supplies and with great difficulty moved his depot across Athabaska Pass to meet Fleming in the Yellowhead area.

Their meeting was a stormy one.

“I felt so disgusted with the engineer-in-chief for having abandoned the line which I knew to be the right one, and at his fault-finding; that I was on the point of leaving the service. I would have done so, had I not known that my men were in a critical position, and relied on me to see them through safely.” He rejoined his party and succeeded in getting them safely to the Yellowhead.

Shortly after, the orders were again changed. It was decided not to use the Yellowhead-North Thompson route. In 1873 Marcus Smith was appointed to take charge of surveys and Moberly was given the task to look for a route between the Yellowhead and Quesnel Lake. Moberly protested in that this was a waste of time. After this futile work he reported to Kamloops and turned over his equipment to Smith and quit. He had become completely embittered and disappointed at the outcome of all his plans.

He did no further work in the final stages of the surveys along the Selkirks and the Kicking Horse Pass. Throughout the rest of his long life he was highly critical of the present route of the CPR which he maintained is more expensive to operate, and more difficult to keep open than the route that he had favored.

Moberly moved to Winnipeg, and was engaged in railway construction and surveys of subsidiaries, among them the line from Winnipeg to St. Paul, Minnesota.

He kept up his friendship with Sir John A. Macdonald, and in their conversations he continually advocated the formation of a private company to build the railroad. He continued to press Prime Minister MacKenzie, that unless the railroad was built in good time, B.C. would secede from the Dominion.

Moberly lived in retirement in a simply furnished room on Hornby Street. Among his circle of friends was Noel Robinson, then a contributor to the Vancouver News-Advertiser. Mr. Robinson published a series of articles on Moberly that aroused interest in the old explorer, and for a time he was in great demand as an after-dinner speaker. The Vancouver Canadian Club made him an honorary life member.

The day before his death in 1915 he insisted in sitting in an easy chair in his room at the hospital. His voice became a whisper, but this did not prevent the old “empire builder,” from venting his outrage by cursing the Kaiser for attacking the British Empire.

– B.C. Biographical Illistrated 1914