THE APEX DIARY OF JACK STOCKS

December 9th, 1961 Penticton Herald

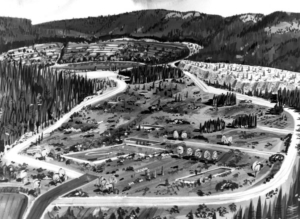

Explosive Apex Growth Could Make Penticton A Winter Mecca

In January 1959, after preliminary discussions on a personal basis, a meeting was called by H.R. McGregor and Jack Stocks and attended by J. Gibson, H. Donald, J. Dalrymple, Walter Powell, A. King, John Leir, P. Workman and Harley Hatfield. This meeting was called purely as a result of a decision to try and revitalize skiing in this area. It was recognized from the first that it was purely a round table discussion and two cardinal points had to be made by this group: Namely it was useless to make any attempt at revitalizing skiing unless adequate snow was available for a sufficient period. Because of this everything below a level of 3500’ in altitude was out of the question and therefore sites were sought which would provide this necessary depth and season. Secondly, the site had to have the proper accessibility.

In January 1959, after preliminary discussions on a personal basis, a meeting was called by H.R. McGregor and Jack Stocks and attended by J. Gibson, H. Donald, J. Dalrymple, Walter Powell, A. King, John Leir, P. Workman and Harley Hatfield. This meeting was called purely as a result of a decision to try and revitalize skiing in this area. It was recognized from the first that it was purely a round table discussion and two cardinal points had to be made by this group: Namely it was useless to make any attempt at revitalizing skiing unless adequate snow was available for a sufficient period. Because of this everything below a level of 3500’ in altitude was out of the question and therefore sites were sought which would provide this necessary depth and season. Secondly, the site had to have the proper accessibility.

It was well known for the years since the end of the war, that a group of ardent skiers led by Jack Stocks and his senior Scouts had rendezvoused at Christmas and New Years for a camping and skiing holiday on Apex Mountain and its adjacent peak, Beaconsfield Mountain. This is an alpine area of between 6000’ and 7000’ altitude with snow from Dec. 1st to Easter. The first problem was therefore solved.

The problems of access were not easily solved as the current logging road to a timber reserve went through private property. After considerable negotiations it became necessary to purchase a large ranch which lay astride the proposed road site in order to gain a right-of-way through this area. This was done at considerable cost to the company (Apex Alpine Recreations Ltd.). However, the right-of-way was obtained and then the company resold the ranch to Orville Ray who proposed developing it into a Dude Ranch in summer and a winter skating and tobogganing site in winter.

In attempting to establish the area as a Provincial Park so as to obtain access to it for construction purposes without having to purchase land, a small difficulty was encountered. It was found that there were several mineral claims and a cabin belonging to Carroll Aikins of Naramata on the land in question. When the problem was explained to Mr. Aikins, he agreed to relinquish his claims so that the areas bounded by these could be incorporated into the new park. Mr. Aikins also agreed to relinquish his rights to the cabin on the stipulation that it should be at the exclusive disposal of the First Penticton Scout Troupe who for many years had used it for camping and skiing. The second problem was solved.

November 8th, 1964

We were up at Apex cutting down a few trees at the top of Juniper near tower 8. It was a miserable day, snowing light, wet snow. We were burning, working in smoke with wet gloves etc.; you know, wet clothes. We climbed back up to tower 9, to the Jeep – puff, puff – tired. Drove down to the lodge tired and stiff, dirty as hell; but sort of exhilarated.

Outside the lodge was a great big Yankee car with a big, fat guy sitting inside all dressed up in a great big car coat with the windows shut tight, listening loudly to the football game while smoking a big cigar. Somebody peers in the window and asks about the game. The guy opens the window a crack, removes the cigar for the moment and says “Great game, the Lions are doing very well!” then closes the window. It just struck me as a perfect example of the typical North American sportsman – Gad!!

As to the road, the Government is spending approximately $30,000 on Green Mountain and Apex roads. They are completely renovating and widening from Boulder Creek down to Ray’s. They should be finished in about 10 days. The hairpin turn where the loggers lost their load is gone! A long culvert with huge fill installed. The logger’s short cut is now the new road and it eliminates three bad corners. At the same time they are working lower down at Allen Grove and the bridge where the road wanders around on the flat dotted with boulders has been staked and is straight as a die. At last, after all those years of saying “It wouldn’t take much”, finally they are doing it.

Ray’s Ranch Lodge is three quarters finished and looks real sharp. He has a huge stone fireplace in it, eleven guest rooms, a dining room and bar. Every two rooms share a bathroom with bath. Ralph West, the new owner, showed us the lodge on Friday. He’s a real neat, young guy; completely different from his predecessor. The concession in our lodge should be 100% better for it.

Apex lodge extension is about 90% completed. A propane power plant is now operating in a new building and the new septic tank has been installed.

The T-Bar is 95% complete with the cable spliced and engine tested. They are installing the drops as well.

The new hill is groomed, almost to perfection. All previous reported piles of trees are either burned or buried, most in the creek at the bottom of the hill.

The second new hill makes a longer, less steep swing to the north and back to the Golden Zone road. It is now being cut out through light timber. The area at the bottom of the T-Bar is changed beyond recognition. It is opened up like a big bowl with new beginner hill running up to the lodge on one side and the T-Bar running up another side with the new hill running up farther over.

August 16th, 1968

The Apex report on the expansion program for 1968: A $100,000 program is now underway. Included is a $51,000 Mueller T-Bar, 2400 feet in length. The top station of this lift is located at the bottom of the present intermediate (Juniper) hill, right near the start of the “Sissy” trail. It runs down from there to the sawmill site. A third bunny type run will connect the parking lot with the bottom terminal of the new lift.

Extensive clearing is being carried out in this new area. For this year, two major new runs will be opened – one immediately adjacent to the new lift, the other will swing out in an arc to the south of the lift and end up down at the mill site. This run will be approximately somewhere below the bottom of the “pit”.

The old T-Bar will be renovated and shortened to about 2400’. The large island of trees on the old T-Bar hill, between the lift and the main run, has been completely removed by bulldozer and changed the character of the hill. It is now very open and wide, and will now be more of an intermediate hill.

Other major improvements will include those to the lodge and the septic system.

An $11,000 Nodwell snowcat is to be purchased for snow grooming, lift maintenance, emergencies etc.

All this work is proceeding well on schedule. The lift line is all cleared and about half of the clearing of the new runs has been done. All the concrete foundations for the new lift have been poured. Unfortunately, just after this was done, Al Menzies came down with appendicitis and he is recovering from surgery. Al was supervising the crew that was doing all this work so I hope he will be well enough to resume this week. We are not contracting any of this out to save ourselves some money.

The Province has repaved the stretch between Kusler’s Ranch turnoff (the bridge) and Allen Grove. The pavement had broken up badly this past year due to poor conditions during the original paving. Also completed is the half mile or so through Allen Grove. So the road is now completely paved to Apex ranch.

The Province has repaved the stretch between Kusler’s Ranch turnoff (the bridge) and Allen Grove. The pavement had broken up badly this past year due to poor conditions during the original paving. Also completed is the half mile or so through Allen Grove. So the road is now completely paved to Apex ranch.

In addition the Government is spending $10,000 on the Apex access road this year. Work to be done will include widening, blasting rock sections and blind corners above Shatford Creek; clearing the lower side of the right-of-way to facilitate widening and snow removal, ditching and gravelling. Ten thousand bucks doesn’t go far over 9 miles, but every little bit helps. If they spend that much every year; we’ll soon have a first rate road up there.

The Finances: The $100,000 required is being raised roughly as follows – $20,000 surplus from last year, $25,000 to be new capital raised by sale of shares and debentures. The balance of $55,000 is to be borrowed from the bank.

We are all very hopeful that this new hill will be a true intermediate ski area and attract the casual family skier.

October 3rd, 1968

Apex is going great guns. I was up there today and there were two big cats working on one hill! What a difference to clearing by hand! The towers are all installed on the new lift and all that is left is to install the sheaves and string the cable. And man, you should see the road. For some unknown and amazing reason, the Provincial budget for the road has increased from $10,000 to $20,000! And they are doing a beautiful job.

November 8th, 1968

Last week I was in Vancouver helping Al Menzies man the Apex booth at the Vancouver Ski Fair in the PNE Showmart. It was the first one I had been to and was really great. Thousands of people went through which is quite amazing when you consider they each paid $1.75 just to get in! All the Pacific Northwest ski areas had booths, as well as ski shops, ski companies, ski boot companies, ski clothing manufacturers etc. They had a huge moving ski ramp which some of the hot shot skiers from the States demonstrated on short skis. Some of them even did flips! Al introduced me to Olympic Gold Medalist Stein Erikson which was a great thrill.

It won’t be long now before the new ski season is underway. They are already skiing at Mt. Baker and Whistler. Our expansion program at Apex is just about complete with the new lift just about ready to go. The Government has spent $30,000 on the road and what a difference. Apex has also bought the snowcat to groom and pack the runs. It can be used for maintenance and breakdowns as well.

January 9th, 1969

On December 29th it turned very cold and remained frigid until about January 1st. It was so cold up at Apex (about 40˚°below) that we had to shut down for five days, and as a result, lost about $5000 in ticket revenues that cannot be regained. After New Years Day, the skiing was quite good, although we could have used a bit more snow. Everybody seems very pleased with the new lift. It really is quite something. When you come barrelling down from the top of the Poma, down the intermediate only to discover another 2400’ of hill below yet to ski!

On December 29th it turned very cold and remained frigid until about January 1st. It was so cold up at Apex (about 40˚°below) that we had to shut down for five days, and as a result, lost about $5000 in ticket revenues that cannot be regained. After New Years Day, the skiing was quite good, although we could have used a bit more snow. Everybody seems very pleased with the new lift. It really is quite something. When you come barrelling down from the top of the Poma, down the intermediate only to discover another 2400’ of hill below yet to ski!

We had a lot of fresh snow this week, so I plan to go up tomorrow after lunch and cut some powder.

January 16th, 1969

Since the holidays, things have improved and we are now getting good crowds at Apex again. The new lift works beautifully and everybody thinks it’s great. I bought myself a pair of Lange boots which I am gradually getting used to. At first they really hurt in front of the ankles.

The snowpack, I would say, is about normal or even a little below normal for this time of year. Apparently a lot of the snow we have been getting down in the valley is confined to the lower elevations. For example, when I left the house to go skiing on Sunday, there was about 5 inches of new snow outside. When I got to the mountain, there was only about two inches. However, the snow is settling nicely and the powder areas are getting good. I can ski the Pipe and the Tongue now without walking out as the connecting trails have been cut out to the new lift.

June 16th, 1969

And now some devastating news about Apex; last night we had our annual shareholders meeting and when it came to new business, a letter was read. It was an offer by five of the existing shareholders (Dawson, Betts, Sharp, Meiklejohn and Raitt) to purchase all the assets of the company! Well, what a bombshell! The offer was $10 a share, same as we paid originally, to be paid 50% in cash and the remaining 50% over the next two years with interest. It was brought to a vote and passed overwhelmingly to sell. There were 25 shareholders at the meeting and a number of proxies.

The whole thing happened so fast that it came as a shock to those of us who had nursed the project along from the onset. The whole thing seemed rather cold-blooded, especially as we were given no previous warning that such an offer was afoot.

The problem was that most of the shareholders seemed anxious to get their initial investment out as they had waited 8 years with no return. Another problem is that there seems to be no end to expansion and demand for more capital. It is increasingly difficult to get it from 50 shareholders, each of whom have a relatively small investment in the company. Another advantage to a smaller ownership group is that you can be damn sure they are going to devote a lot of time to the business to make sure it goes. There is some talk of Sharp becoming the new manager with Menzies reverting to the ski school. It’s the end of an era.

Feb. 3rd, 1970

Apex Alpine Recreations Ltd. has sold to five of the shareholders. It was a bit of a shock at the time, but it was probably for the best. Most of the original 50 shareholders were involved with a company that they weren’t spending full-time at and that made for some problems. Also it was always difficult getting ones ideas across (and I was president for several years) and trying to convince the board of directors.

Apex Alpine Recreations Ltd. has sold to five of the shareholders. It was a bit of a shock at the time, but it was probably for the best. Most of the original 50 shareholders were involved with a company that they weren’t spending full-time at and that made for some problems. Also it was always difficult getting ones ideas across (and I was president for several years) and trying to convince the board of directors.

Apex continues to improve and expand under the new ownership. I no longer have any involvement in the company.

Last year some major improvements were made to the lodge, including building overnight guest accommodation. This year a $100,000 chairlift replaced the original T-Bar, installed in 1964.

I am still skiing regularly.

Editors note:

Jack’s contribution was never forgotten. His dedication to his Scout Troupe, Apex Alpine, the Downtown Business Association and to his craft as a photographer, knew no bounds.

Jack Passed away in 1979 after his best business year, ever. It was an untimely death to cancer.

Apex remembered him with the dedication of the “Stocks Triple Chair” in February of 1982.

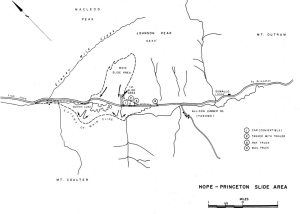

There was a little more snow than expected, thought Steph as he climbed the hill toward Allison Pass. He saw lights in his mirrors so he politely signaled the car to pass. It was a nice bright yellow Chev convertible and the girl in passenger seat gave him a little wave. It quickly disappeared ahead of him. He had passed three semi trucks heading to Princeton but other than the yellow car, there was no other traffic.

There was a little more snow than expected, thought Steph as he climbed the hill toward Allison Pass. He saw lights in his mirrors so he politely signaled the car to pass. It was a nice bright yellow Chev convertible and the girl in passenger seat gave him a little wave. It quickly disappeared ahead of him. He had passed three semi trucks heading to Princeton but other than the yellow car, there was no other traffic. “We better get to the trucks, now!” screamed Dennis. “We’ve got to get out of here”.

“We better get to the trucks, now!” screamed Dennis. “We’ve got to get out of here”.

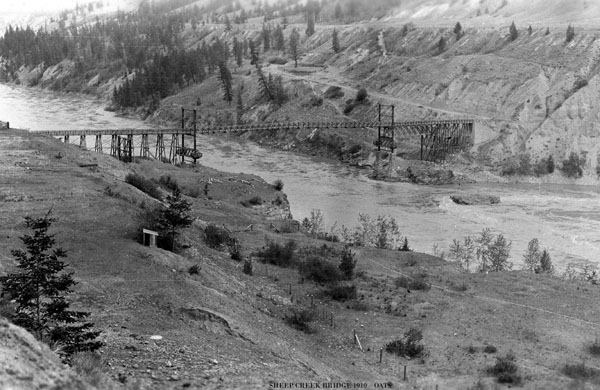

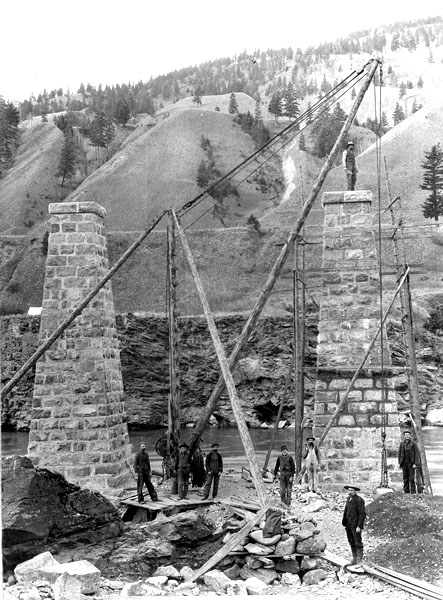

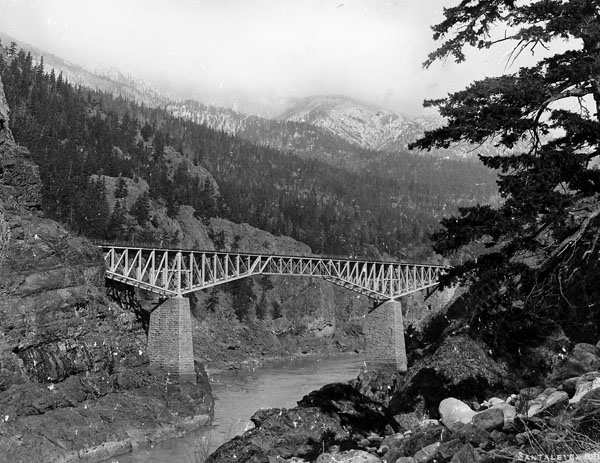

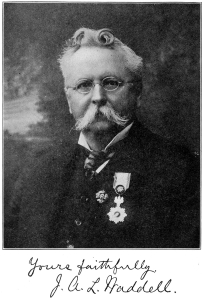

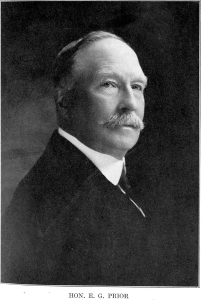

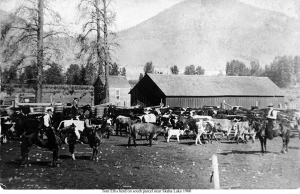

Now let’s put this project into perspective. The Provincial Government of the day led by Premier Edward Prior; was petitioned to build this bridge by a voting population of 40 white males, the total eligible voters of the Chilcotin. They insisted the bridge would bring prosperity to the entire heartland of the Province, and enable the production of cattle and sheep to feed the world.

Now let’s put this project into perspective. The Provincial Government of the day led by Premier Edward Prior; was petitioned to build this bridge by a voting population of 40 white males, the total eligible voters of the Chilcotin. They insisted the bridge would bring prosperity to the entire heartland of the Province, and enable the production of cattle and sheep to feed the world.

The Legislature was livid and called for his head, but Premier Prior wouldn’t resign. Prior’s gentry was his downfall as he stated he was privileged as a Militia Colonel

The Legislature was livid and called for his head, but Premier Prior wouldn’t resign. Prior’s gentry was his downfall as he stated he was privileged as a Militia Colonel

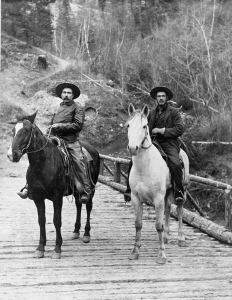

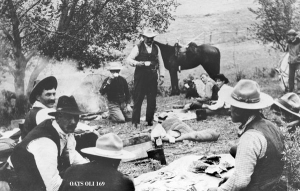

Wednesday, May 17. We had a very unpleasant trip today over a rough and mountainous country, by far the worst trail I have yet seen in this country. We camped without about 6 miles of the Mission.

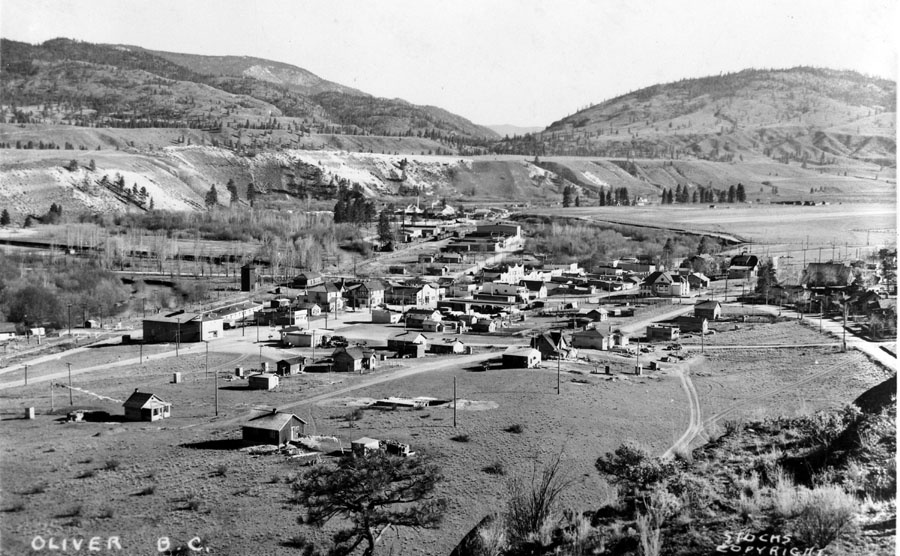

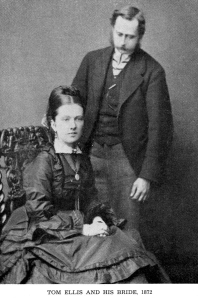

Wednesday, May 17. We had a very unpleasant trip today over a rough and mountainous country, by far the worst trail I have yet seen in this country. We camped without about 6 miles of the Mission.  Thursday, May 25. We got as far as Penticton this evening, and I had a good look at the place, but I did not like the look of it, although everyone says it is a very good place for wintering cattle.

Thursday, May 25. We got as far as Penticton this evening, and I had a good look at the place, but I did not like the look of it, although everyone says it is a very good place for wintering cattle. His diary does record that Andy and Ellis planted “…some potatoes, for seed,” at Osoyoos, and his daughter, Dr. Kathleen Ellis told this writer that her father made “…several trips back from where he was working, to tend the potato patch….”

His diary does record that Andy and Ellis planted “…some potatoes, for seed,” at Osoyoos, and his daughter, Dr. Kathleen Ellis told this writer that her father made “…several trips back from where he was working, to tend the potato patch….”

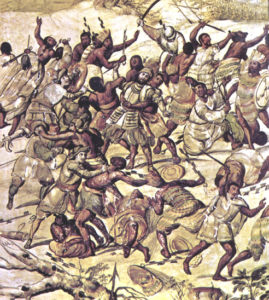

the Columbia River was actually a bay, the conquistadors traveled upstream hoping to find a crossing away from the marauding Chinookans. But the river was very wide and went on forever. These men were seasoned soldiers with amazing survival skills who carried their faith in God as an additional sword. Without horses they would have made no more that 10 or 15 miles a day along the banks of the Columbia. Coming through the deep gorge of the Cascade Mountains, it would have taken months to just make it as far as The Dalles. From there the river got calm and the small tributaries were easy to cross. The land stretched out and became desert like. The local natives were friendlier but cautious of these dark, hairy travellers with metal weapons. The soldiers would have traded for pack dogs with the Chelan people as the Spanish had skills with pack animals of all kinds. Horses would not be seen in this northland for another 50 years.

the Columbia River was actually a bay, the conquistadors traveled upstream hoping to find a crossing away from the marauding Chinookans. But the river was very wide and went on forever. These men were seasoned soldiers with amazing survival skills who carried their faith in God as an additional sword. Without horses they would have made no more that 10 or 15 miles a day along the banks of the Columbia. Coming through the deep gorge of the Cascade Mountains, it would have taken months to just make it as far as The Dalles. From there the river got calm and the small tributaries were easy to cross. The land stretched out and became desert like. The local natives were friendlier but cautious of these dark, hairy travellers with metal weapons. The soldiers would have traded for pack dogs with the Chelan people as the Spanish had skills with pack animals of all kinds. Horses would not be seen in this northland for another 50 years.

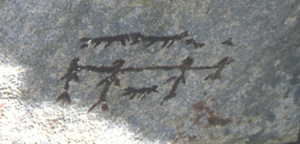

The discovery of a rare native breastplate; hammered from copper, in an old burial site near Keremeos, also lends credence to the Spanish story. The piece is heavily perforated to look like chain mail. Where did the Similkameen Band get the idea of armor plate? It was singular to the Keremeos region and some historians contend that the Indians simply copied the Spanish mail they had seen or been told of, which had proven nearly impenetrable to arrows during the battles.

The discovery of a rare native breastplate; hammered from copper, in an old burial site near Keremeos, also lends credence to the Spanish story. The piece is heavily perforated to look like chain mail. Where did the Similkameen Band get the idea of armor plate? It was singular to the Keremeos region and some historians contend that the Indians simply copied the Spanish mail they had seen or been told of, which had proven nearly impenetrable to arrows during the battles. Finally, in 1863, the ruins of a large building were discovered in the Kelowna area. The size of this massive structure, estimated at around 35’ by 75’ indicated that it had once been a winter quarters and even in 1863 was very old. Was this a building used by local peoples for ceremonial purposes or was it the place the legend says was used by the Spanish when they purportedly wintered near Kelowna?

Finally, in 1863, the ruins of a large building were discovered in the Kelowna area. The size of this massive structure, estimated at around 35’ by 75’ indicated that it had once been a winter quarters and even in 1863 was very old. Was this a building used by local peoples for ceremonial purposes or was it the place the legend says was used by the Spanish when they purportedly wintered near Kelowna?

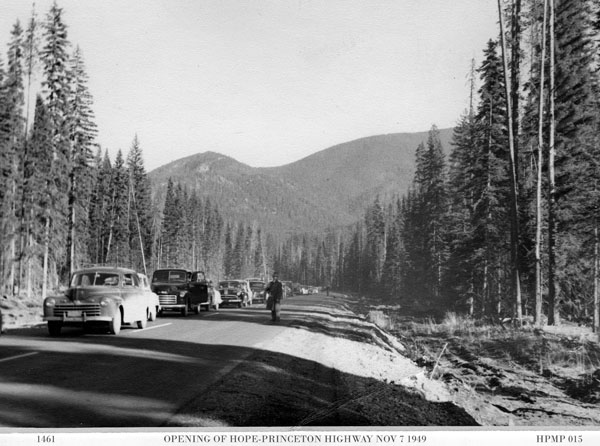

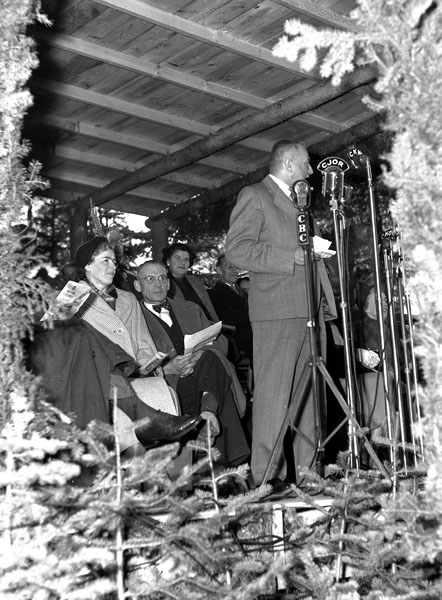

At the height of the depression, the Federal Government provided funds for construction of the road and the Province put into effect a work relief program. 40 relief camps were set along the route and workers came from all over Canada. These men worked year round in camp shacks where snow drifted in and hygiene was rare. But they did get fed regularly and could send money home to their families. Some never

At the height of the depression, the Federal Government provided funds for construction of the road and the Province put into effect a work relief program. 40 relief camps were set along the route and workers came from all over Canada. These men worked year round in camp shacks where snow drifted in and hygiene was rare. But they did get fed regularly and could send money home to their families. Some never

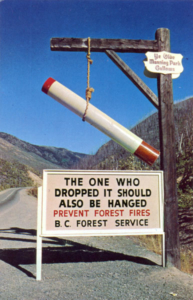

There is confusion about the history of this sign. Here’s the true story.

There is confusion about the history of this sign. Here’s the true story.